Lifted from the City

It’s a rainy night in Hong Kong. Prepared for work, the young man leaves the apartment. The bus takes him down Lockhart Street. Neon signs surround him. He passes CLUB CELEBRITY, the OK, CLUB HOT LIPS, BROADWAY SEAFOOD and the PALACE SAUNA, with other signs flashing by too quickly to make out. The night is red, green, yellow, pink and baby blue. There are signs in Chinese. There are signs in English. There are horizontal lines, vertical lines, wavy lines, small circles, half circles, big circles, squares and circles inside squares. The puddles on the street reflect the colours, the letters, the lines and the symbols, as do the bus’s windows. In the rearview mirror, the young man’s face appears: sleepy, dreamy, innocent even. He’s on his way to kill some people.

We’re watching Fallen Angels, the classic 1995 film directed by Wong Kar-Wai, in which actor Leon Lai plays a professional assassin. In just a few seconds, Lai’s character is going to get off the bus and walk into a restaurant to do his job. He will leave half a dozen bodies behind, only to return to the same bus line and go back up Lockhart Street, passing through the neon again. It is one of the most memorable sequences of a film set at night and energised by a multitude of city lights: jukeboxes, cigarette tips, illuminated clocks, elevated trains, fluorescent lights, plastic fast-food signs, TV screens in small apartments. Like a multiple personality, the city splits up into all sorts of glowing things. Some move around. Some stay in one place. All of them are impossible to ignore. And yet, neon’s transcendent beauty seems particularly compelling. It makes us forget the bodies our melancholic killer has left behind. The pulsating tubes lift us from the city’s actualities.

Then again, they are very much a part of them. It is no accident that neon lights play a key role in Wong Kar-Wai’s electrifying film, designed, in part, to capture the spirit of Hong Kong. 1 From the late 1950s onwards, the colourful, gas-filled glass tubes had provided the city’s visual language. ‘A million neon signs light the streets proclaiming their messages in every colour’, states the Hong Kong Report for the Year 1964. 2 Local creativity, combined with the influence of 1930s and 1940s Western visual culture and low production costs, freed designers to embark on new and adventurous projects. 3 In Hong Kong’s dense and crowded spaces, restaurants, small shops and department stores competed for attention. Neon became a key tool. Business owners used signs that were larger than their competition’s. Or they chose devices so memorable that they turned into urban landmarks. The Emperor Watch & Jewellery sign, jutting over Nathan Road, and the airborne neon cow of Sammy’s Kitchen are two of the most prominent examples. 4 The tubes made for fashionable flashiness, but they also established traditions. As historian Simon Go notes, entrepreneurs would invest in a ‘sign that would last’, to be passed on from generation to generation. 5

However, neon has played an ambivalent role ever since the gas first showed its breathtaking red hue upon its discovery in a London laboratory in the late nineteenth century. On the one hand, the flashing tubes strike us as quintessentially urban. Their pulsating colours have fired up streets and squares around the world. Countless films, stories and works of art have used neon to portray these streets and squares as vibrant, often violent, realms. The arc spans from the small-town America of the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life to Vladimir Nabokov’s provocative novel Lolita (1955), and from Ridley Scott’s sci-fi thriller Blade Runner (1982) to works by contemporary artists such as Bruce Nauman and Tracey Emin. On the other hand, glowing tubes never really shaped cities in the way that steel, concrete or giant LED screens have done. Neon tubes are much too small and brittle to take on this kind of force. Filled with natural gas and fashioned by diligent craftsmen, the glass tubes embody an elegant fragility at odds with metropolitan monumentalism. Thus, neon has always flickered on both the inside and the outside of urban cultures. Lockhart Street sadly proves this point. All the signs working their magic in Fallen Angels have now disappeared.

The History of a Natural Product

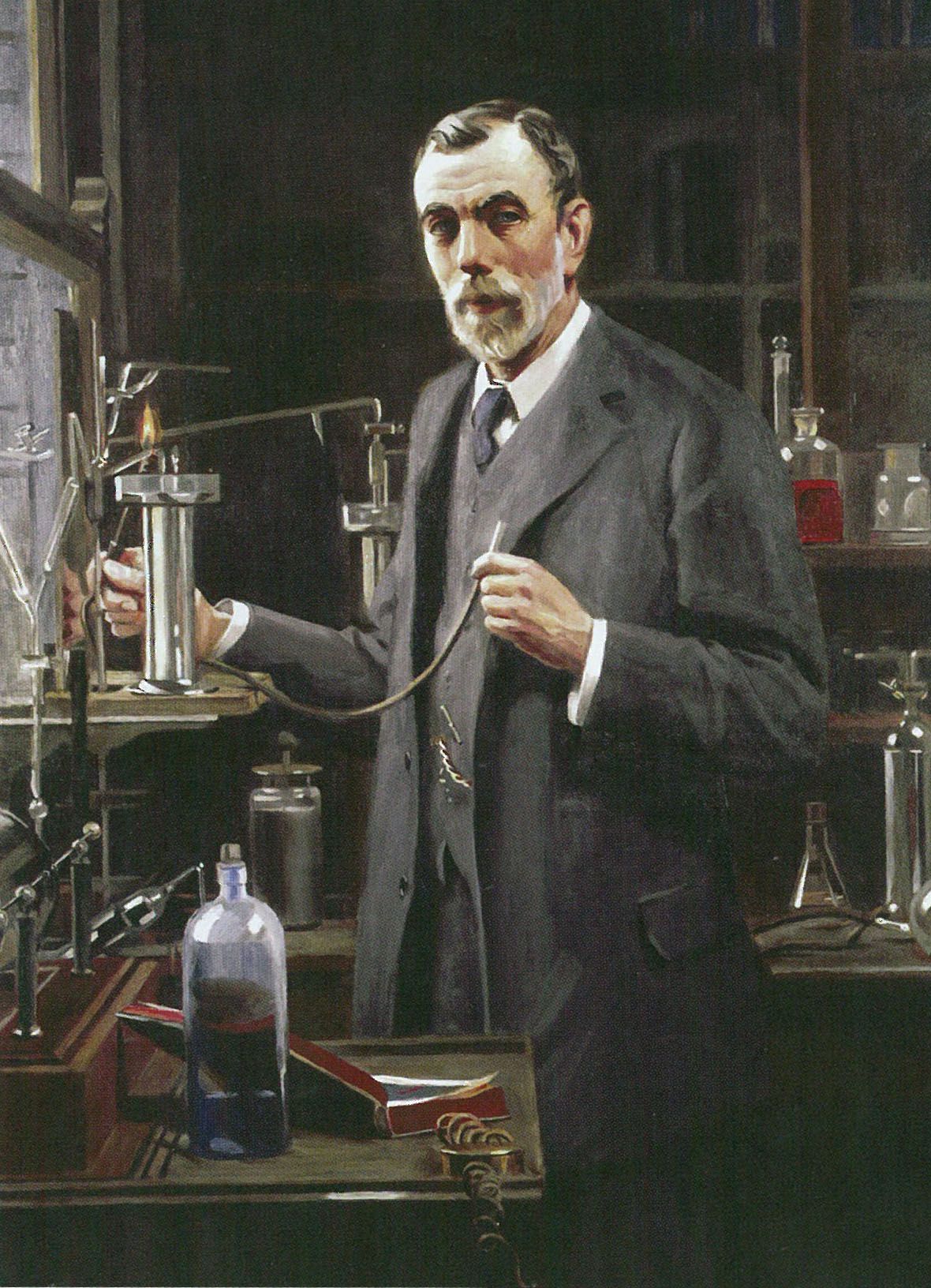

The tension described here is mirrored in basic chemistry. Neon makes up 0.00046 per cent of the atmosphere. There’s nothing synthetic about it. It’s all around us, and in our lungs. William Ramsay, British chemist and future Nobel laureate, discovered the gas in 1898, in a campaign to fill the last gaps of the Periodic Table. In order to identify the unknown substance, he placed it in a glass container and charged it with electricity. Soon he saw a ‘blaze of crimson’ that held him and his colleagues ‘for some moments spell-bound’. They were amazed by the ‘dramatic way’ the gas and its ‘magnificent spectrum’ appeared in their apparatus. 6 In this period, London, like other great European cities, was rapidly turning into a capital of electric light and illuminated advertising. But Ramsay didn’t have commercial purposes in mind. The father of neon compared the marvellous glow to a natural phenomenon: the Northern Lights, the breathtaking spectacle in the polar region that occurs when electric currents color the skies. 7 Neon, often used as a metaphor of artificiality, began its career as an organic product.

Neon, often used as a metaphor of artificiality, began its career as an organic product.

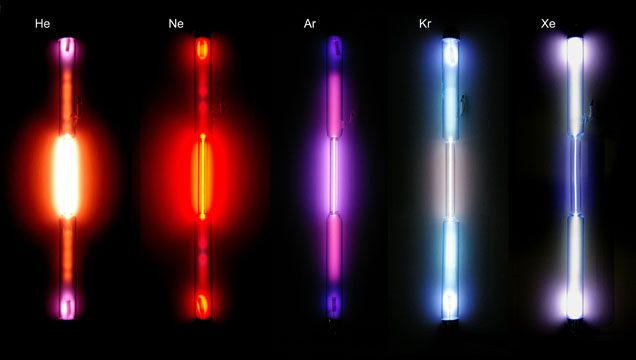

Things changed in Paris. Georges Claude, French engineer and entrepreneur, turned electric tubes into commercial signs. In 1912, he produced the first neon letters advertising a business: PALAIS COIFFEUR gleamed over Boulevard Montmartre. Claude narrowed the glass containers to intensify neon’s glow. Experimenting with other noble gases, he was able to offer a range of colours to his customers: argon gleamed violet, xenon pale blue, helium pink and krypton silvery white. Mixtures of these gases broadened the palette, and tinted glasses and coloured metal added more options. At this point, there was nothing garish about neon. Observers found that the new tubes seemed much easier on the eye than the round and blinding incandescent light bulbs that earlier advertising had used. Some writers compared neon’s qualities to the softness of glowing candles. Claude’s slender tubes illuminated the Paris Opera, banks, luxury stores and even churches. They were seen as signs of sophistication.

In 1920s Paris, people saw the City of Light glow and just had to take a part of it home. A Los Angeles car dealer returned from the French capital in 1923 and installed luminous orange letters spelling out the name PACKARD high above the streets of his hometown. Neon had arrived in the United States, and its conspicuousness stopped traffic. But its global success depended on the franchising system that Georges Claude developed. Holding crucial patents, he sold regional licenses to customers everywhere on the planet. As early as 1930, Claude’s enterprise boasted ‘Claude Neon Associated Companies’ across the United States and Canada, and in Mexico City and Havana, Cuba. There were branches in Australia, Neon signs, Paris, 1931. New Zealand, Tokyo, Osaka and Shanghai. 8 And in 1932, a Claude shop opened in Hong Kong. A company magazine — the Claude Neon News — updated its readers on the latest developments in neon’s global story and the significant legal trouble awaiting anyone who would infringe on Claude’s copyrights. In early 1930, a Claude Neon News article praised the ‘New Lights in Tokyo’. It counted four signs: One advertised an automobile company, another a newspaper and still another a textbook publisher. The fourth, installed in the Asakusa entertainment district, showed the way to the ‘Headquarters for Beef Pot’. 9

Though neon quickly spread around the world — the first neon sign in China appeared in 1926, advertising Royal typewriters on Shanghai’s Nanjing East Road — the epicenter, in the 1930s, was the United States. Here, the tubes became an integral part of a vibrant popular culture battling the profound economic crisis caused by the Great Depression. The new, glamorous American movie theatres depended on neon. A Hollywood entertainment palace spelled out its philosophy in glowing letters: ‘Through these portals pass the most beautiful girls in the world.’ In 1930s Times Square, the center of New York nightlife, neon turned into the key fixture of the most elaborate visual effects ever to emerge from urban culture. Advertisements showed neon fish as big as whales. Neon roses, 30 metres high, sprang up and faded, again and again. A coffee advertisement using neon and the real smell of coffee turned New Yorkers’ heads. From any corner of Times Square, an attentive pedestrian could make out 300 different neon installations. In this new era of coloured lights, Broadway, previously known as ‘The Great White Way’, was rechristened ‘Rainbow Ravine’.

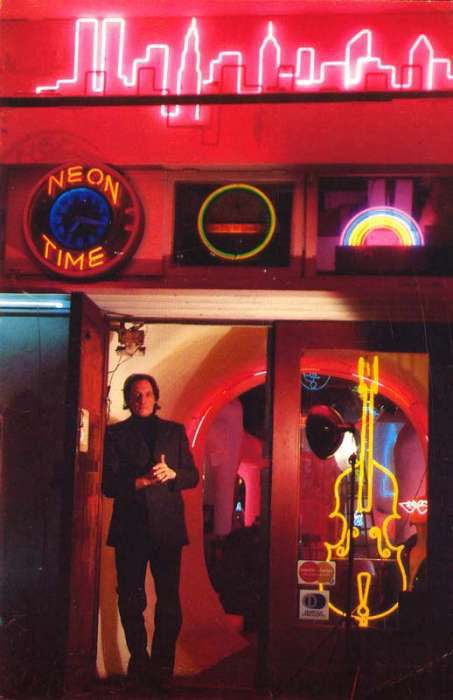

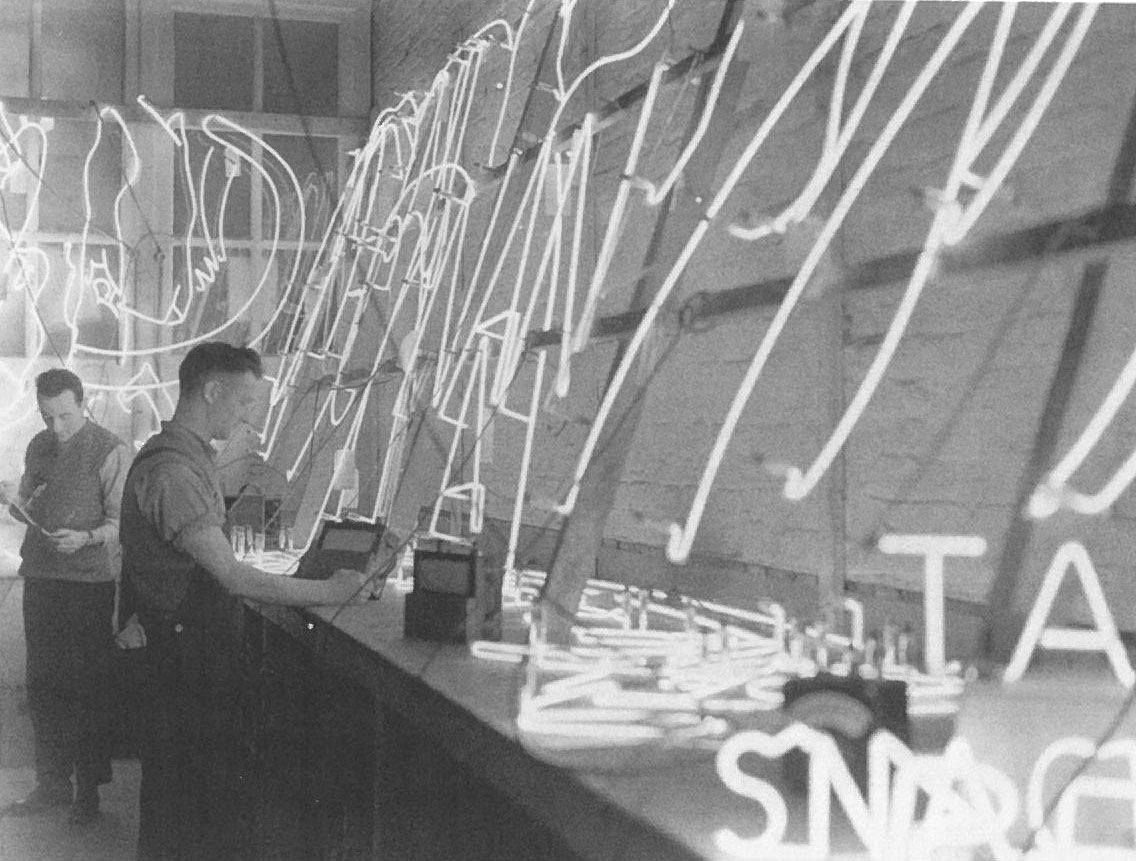

Times Square gave neon larger-than-life proportions. And yet, the overwhelming number of signs had a decidedly human touch — particularly after Claude’s patents ran out. Small workshops produced these tubes. Craftsmen designed letters and symbols according to the needs of their customers. Once they had settled on a design, they used their breath to create the glass containers and, ever so carefully, their hands to form the desired shapes. ‘Good glass-bending looks deceptively easy’, explained Rudi Stern, the New York neon guru who founded the storied workshop Let There Be Neon in 1972. ‘But to bend a simple circle might require the knowledge and skill of twenty years’ shop experience.’ Stern emphasised the significance of breath and touch. It takes rich expertise, he said, to ‘sense the heat building up in the glass’. One has to know the right moment to shape the fragile tubes into the right form. 10 To work with neon tubes requires forms of mastery endangered by the industrial age. In his recent study The Craftsman, sociologist Richard Sennett praises ‘craftsmanship’ as a way of life, a commitment ‘to conduct life with skill’. 11 In their workshops, neon-sign makers kept this way of life intact.

Yet demand for these abilities would soon begin to fade. In the 1950s, cities in the United States were redesigned to suit automobiles rather than pedestrians. The increasingly suburban nation required bigger signs. Made of plastic, these were less fragile and more powerful than their neon counterparts. Plastic signs were shaped by machines and by the new advertising philosophies of motel or restaurant chains. By and by, neon disappeared from the visual culture of middle-class America — relegated to hanging around, literally, above the doors to cheap bars and motels. It flickered in neighbourhoods untouched by the growing prosperity of the postwar years. There’s a tight connection between inner-city decay and neon’s decline. The glamorous American downtowns of the first few decades of the twentieth century changed into wastelands. Hence, an advertising technology once used to decorate luxury stores and churches turned into a symbol of the rundown and the red-light district. Previously, neon had advertised the ETERNAL SUNSHINE and WONDERFUL TREASURES of Egypt high above Parisian streets, while in Times Square, a lighting fixture had asked passersby: HAVE YOU WRITTEN TO MOTHER LATELY? Now, decaying, carelessly treated and a gadget of yesteryear, neon promised accommodation in a dubious HOT L or the company of GI LS G RLS GIR S. Las Vegas, Nevada, emerged as a neon city in the 1950s and 1960s. But its hotels and casinos moved on to other forms of spectacular advertising after just a couple of decades. Meanwhile, though Asian cities had largely been spared the United States’ urban decline, they would not be immune to neon’s seedier associations — in the form of pawn shops, massage parlours, hostess bars and other venues of ‘ill-repute’. Neon had hit a low.

By and by, neon disappeared from the visual culture of middle-class America — relegated to hanging around, literally, above the doors to cheap bars and motels.

Neon’s Friends and Foes

Writers and intellectuals resuscitated Claude’s tubes. But they did so inadvertently, largely because neon embodied a worldview they detested. Suspicious of mass culture’s energies, a generation of postwar thinkers discovered the glowing devices to be useful metaphors of modernity’s superficial flashiness. Composing a theory of music in the late 1940s, Theodor Adorno attacked the ‘all-powerful neon light style’ of the culture industry. To Adorno, genuine art was a deep, dark and complex counterforce to the superficial terror of brightness, commerce and entertainment. (Guy Debord’s 1967 concept of the ‘society of the spectacle’ departs from a similar idea: visual effects hypnotise consumers, reducing their world to a conglomeration of images and products). 12 In the realm of fiction, Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 masterpiece Lolita used neon as a powerful metaphor. The novel exposes the violent, obsessive mind of its obnoxious narrator, who rapes the object of his desire ‘in the neon light [. . .] coming through the slits in the blind’. 13 In the early 1990s, attacking consumerism and technology, cultural critic Theodore Roszak composed an essay titled ‘The Neon Telephone’. 14 American sociologist Lauren Langman’s influential paper ‘Neon Cages’ depicts modern consumer spaces as territories of techno-fascism, treating shopping malls as dreamlike environments where everything is controlled. 15 Studying the work routines of cosmetic saleswomen in Taiwan, sociologist Pei-Chia Lan uses Langman’s terminology. Lan explores the new ‘neon cages’ of women permanently exposed to bright lights. They must always perform, and are always under surveillance. 16

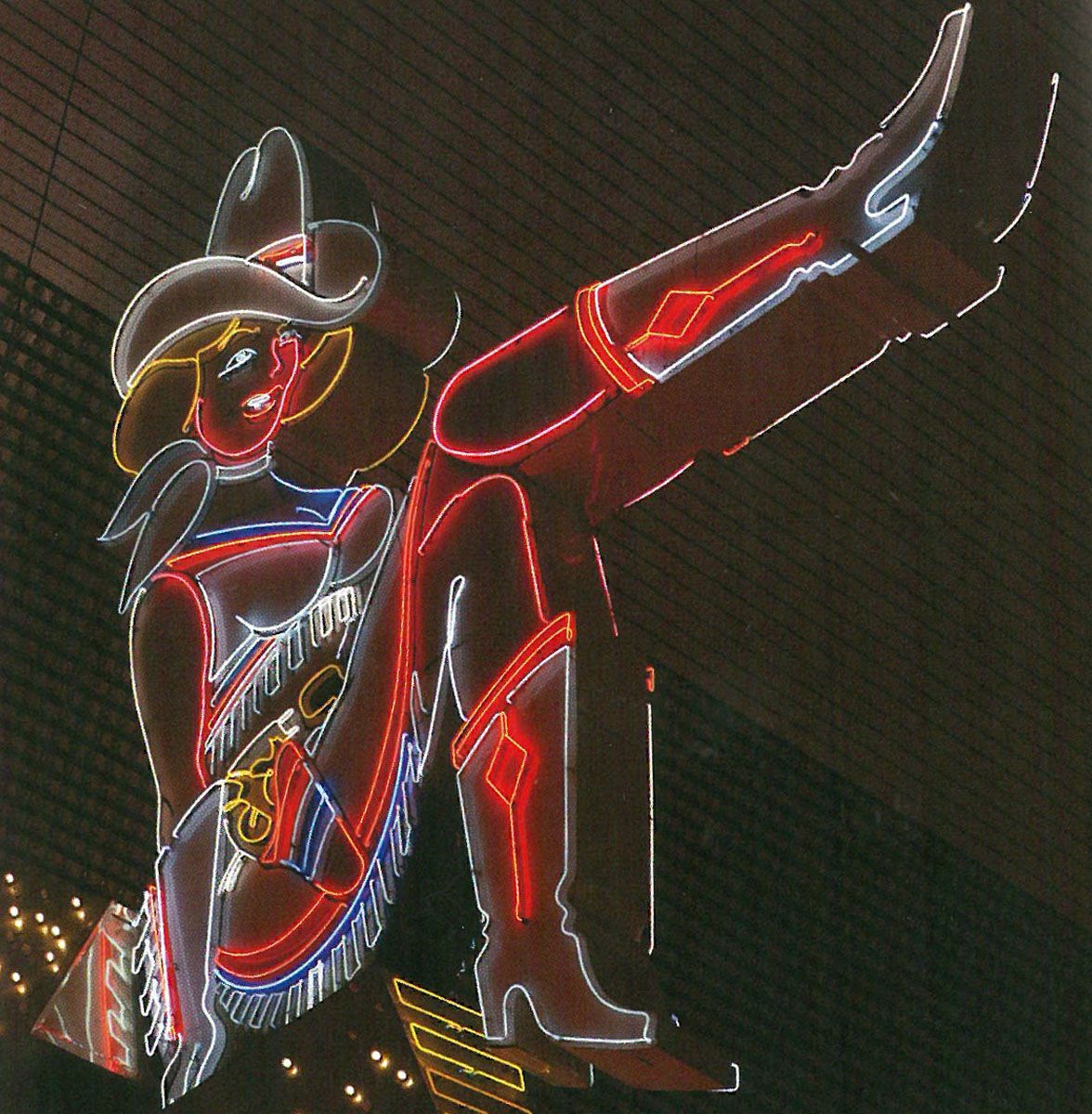

While suffering as an actual technology, neon as a metaphor became ever more expansive. Langman’s and Lan’s ‘cages’, for instance, may not be illuminated by neon at all — nor by argon or xenon or any other noble gas that Georges Claude once tinkered with. Rather, these sociologists seem to address spaces lit not by neon but by fluorescent tubes (the term doesn’t sound half as elegant). Of course, even ‘good old neon’ isn’t all that innocent. 17 Neon enthusiasts need a certain willful naivety to move from pulsating sauna to pulsating sauna, from CLUB CELEBRITY to CLUB HOT LIPS, and to think of these signs purely as signs. After all, their beauty helps us ignore the bodies at work and the bodies for sale. It is a somewhat flippant (though inspiring) form of postmodern flirtation to follow Learning from Las Vegas and to praise a neonised gambling hell in the Nevada desert as the most interesting place that modern architecture has ever conceived, as that 1972 architectural manifesto did. 18 Surely, we are a bit too eager to ignore urban realities, our eyes always drawn to some gimmicky capitalist spectacle that just happens to look terrific — and even more terrific in the rain. It seems healthy, then, that certain cultural critics take a different approach. Bruce Bégout, for instance, a French philosopher once stranded in Las Vegas, looked at a giant neon cowgirl known as ‘Vegas Vickie’ and saw only the ‘boundless cruelty’ of a ‘celestial and mechanical whore’. 19

All in all, though, neon’s story is a bit more nuanced than that. Glowing tubes may have shaped grotesque cowgirls. But they were also used, in all sorts of contexts, by groups and individuals creating niches for themselves, working with neon in order to gain footholds in urban spaces. In neon workshops, artisans kept an independent craft alive for as long as they possibly could. A fragile lighting technology with a limited range, neon tied neighbourhoods together. And some authors noticed. In late 1940s Chicago, the novelist Nelson Algren coined the phrase ‘neon wilderness’. With great humanist empathy, he describes communities of poor, marginalised city dwellers who struggle to resist the centrifugal forces of modernity in the neon-lit bars that they have made their homes. 20 Peggy Lee, a jazz singer and Algren’s contemporary, co-wrote and sang the tune ‘Neon Signs (I’m Gonna Shine Like Neon Too)’, an upbeat number celebrating the city as a joyful place. 21 These texts do note that neon distracts from urban actualities. But they also insist that the glowing letters and symbols refer to communal institutions that can transform cities from the ground up.

In this context, neon’s most recent transformation began. The first generation of light artists arose in American cities during the 1960s. They lived and worked in neighbourhoods caught in rapid de-industrialisation. Blue-collar work disappeared from these spaces. Hardware stores, industrial objects and the very idea of craftsmanship seemed dated. These artists used the glass tubes as detritus — along with a range of other seemingly useless materials. Art historian Joshua Shannon describes this late twentieth-century movement as an act of ‘willful resistance’ to the service industries now taking over artists’ environments. 22

Neon seemed like a quaint and useless technology. And then it turned into an inspired material for conceptual art, confessional installations and minimalist experiments. Bruce Nauman’s installations hypnotised audiences with the most basic linguistic and corporeal forms. Dan Flavin — though working with neon-free fluorescent tubes — developed a new language to represent material in space. Joseph Kosuth conducted philosophical investigations in neon. Artists such as Lili Lakich and Chryssa used the signs to create life narratives in tight connection to modern urban spaces. At the turn of the twenty-first century, British artist Tracey Emin turned to neon when looking for a sensual and fragile material with which to display intimate notes in public spaces. She had first encountered neon in Margate, a decaying English seaside resort. Drawn to neon’s symbolic connection to cities in crisis, contemporary artists did more than just breathe new life into yesterday’s advertising technology. Displayed in streets and squares, in art spaces and in front of them, light art — neon art — has helped revitalise cities themselves.

Neon seemed like a quaint and useless technology. And then it turned into an inspired material for conceptual art, confessional installations and minimalist experiments.

In Hong Kong, the story may run along similar lines. Neon has been losing significance here. LED makes for brighter, cheaper light. The tubes had first reached Asia in Georges Claude’s great international franchising scheme, but ironically, they’ve started to vanish because today’s global corporations want their advertising to be the same for each and every franchise branch. 23 In contrast, Hong Kong’s independent restaurants, adorned by neon on the outside, and offering sustenance on the inside, remain nourishing places where social and family ties are made. Their gleaming signs link a dynamic metropolis back to the small fishing village it once was. Neon still pulsates: a part of the city and a stranger to it.

The gunman passing through Lockhart Road on his way to his job in Fallen Angel; Image courtesy Block 2 Pictures Inc. All rights reserved.

The gunman passing through Lockhart Road on his way to his job in Fallen Angel; Image courtesy Block 2 Pictures Inc. All rights reserved.