Foreword

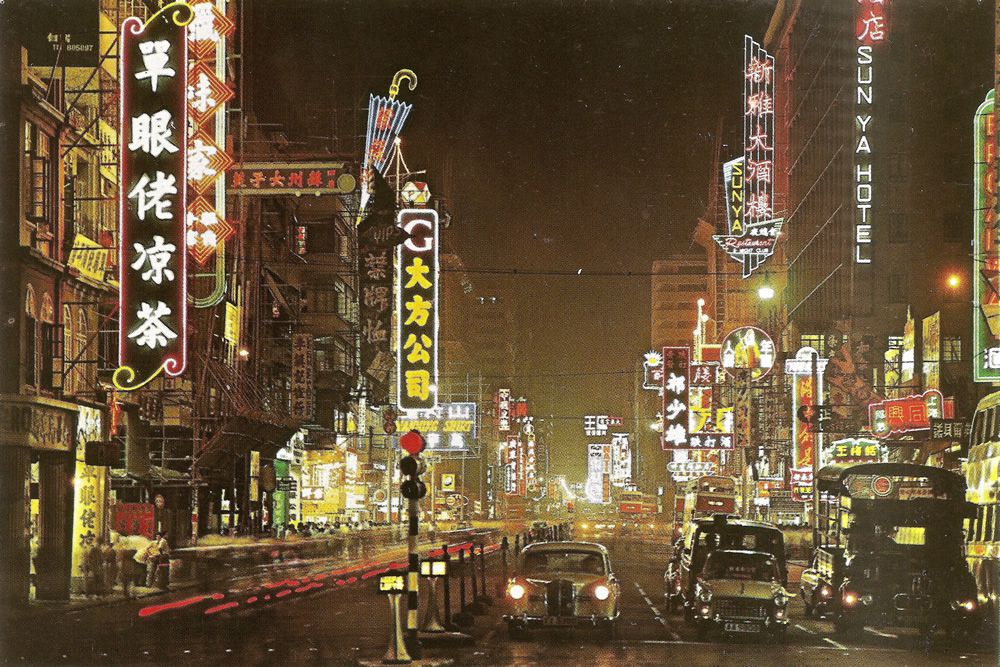

‘“Let there be light”, God said, and there was light.’ Humankind, however, learned to burn kerosene to light up the urban outdoors only relatively recently. It was not until the early nineteenth century that kerosene lamps gradually appeared in streets and arcades and on bridges in cities in the West. The dawning of “urban colourogy” would take yet another century. In 1898, scientists discovered neon, a colourless and odourless gas that, when injected into electrified vacuum tubes, emits red light. The term ‘neon light’ was then vividly rendered into Chinese, partly as a loanword, as ‘rainbow-hued light’. With intense colour beaming even under the worst of weather conditions, neon lights soon found widespread use throughout the city, as air and sea navigation beacons and as logos in the commercial arena. Neon signs first lit up hair salons and opera houses in Paris in the 1910s. After arriving on the scene in Los Angeles in the 1920s, the neon sign soon spread throughout the United States, giving birth to the spectacular neon-scapes in New York’s Times Square and The Strip in Las Vegas in the 1930s and ’40s. This was also when the neon-light trend came east, with modernising metropolises Shanghai and Tokyo being the early adopters, and Hong Kong following suit by the 1950s. The marriage of Western technology and square-block Chinese logograms began to adorn our city’s night sky in rainbow colours. No doubt the history of technological development deserves a whole separate essay; mine will dwell on the cultural imagery of the neon sign in artistic texts and urban landscapes.

A Palette of Lights, a City’s Evening Make-up

If one were to picture the city’s night sky as a palette of lights, or as a woman’s evening make-up, then the ubiquitous illumination at nighttime would be the city’s foundation and the faint yellow lights its alluring but subtle dabs of shades. The colourful, brilliant neon lights would be the city’s layered, showy make-up, worn as though in anticipation of a lavish nightly banquet hosted by the prosperous world of commerce. Neon nestles amid the city’s forest of signboards, blanketing every corner where consumer activities thrive. For over half a century, Hong Kong has been adorned with such splendid make-up, an urban spectacle unique among the great cities of the world.

The visual stimulus of the neon sign seems to reflect the prosperity that fuels urbanites’ desires, or, rather, the sign per se is the bait to desire.

Neon signs in Hong Kong are used across a wide range of businesses: drugstores, banks, restaurants, bistros, video game parlours, currency exchanges, etc. — too many to list here. Yet, the imagery of the neon sign, or its symbolism, more often than not stands out as a hallmark of prosperity and resplendence, especially when set against the jet black sky. Even as nocturnal creatures scurry out of their caves, the city at night does not come alive as a stage without the neon sign as its limelight. The visual stimulus of the neon sign seems to reflect the prosperity that fuels urbanites’ desires, or, rather, the sign per se is the bait to desire. Capitalist society is predicated on city dwellers’ desire to consume; ‘the city that never sleeps’ thus becomes synonymous with ‘the city of desire’. In this regard, no other form of illumination is more suited to lighting up the city than neon. It is precisely the interplay of the dazzle and the desire that made the neon-lit spectacle of New York’s Times Square the ideal foil for faceless loners such as Robert De Niro’s character Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, (1976). Only in this urban mirage would neon lighting ‘stab’ the eyes — as in Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘The Sound of Silence’ (1964): ‘When my eyes were stabbed by the flash of a neon light | That split the night | And touched the sound of silence.’ This is a feeling that speaks to our experience as city lights have become, if you will, a mobile visual aura, an urban sensibility. The mentality and materiality of the city are constantly shaping each other.

The Literary Hotel, the City of Desire

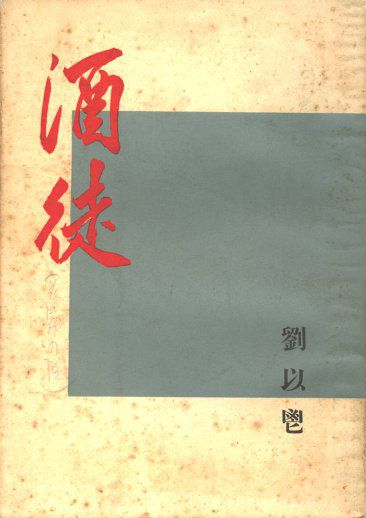

Under the dazzle of neon, there falls dejection; in the shadow of radiance, there lies loneliness, accompanied by an unmistakable undercurrent of desire. These variegated representations of the neon sign are commonly adapted, scrutinised and magnified in local literature, movies and music. Any number of notable examples spring to mind. In Love in a Fallen City (1943) by Eileen Chang, when Bai Liusu, the female protagonist, docks at Hong Kong for the first time, Chang describes Bai’s fixation on the colliding colours of shop signs reflected on the blue-green waters. Perhaps neon signs were not as omnipresent then as now, for Chang gives no direct depiction of them. While I have no way of ascertaining when the neon sign first appeared as a singular imagery in Hong Kong literature, I can say that one of its earliest appearances occurred in Cao Juren’s 1952 novel, The Hotel. Set in 1949, the year when the Chinese Communist Party took control of the mainland, the story opens with a young man who, after having fled south with his father to Hong Kong, toils as a shoe-shine boy at M Salon and becomes acquainted with a call girl and fellow refugee working next door. In one scene, Cao describes how the young man, upon stepping out from the side entrance of the salon, looked up and spotted a neon sign with the characters ‘Ching Wah Ballroom’. The fictional hotel of the novel’s title is a hotbed of lust located on Nathan Road, long the turf of neon signs, but of course signs are everywhere and anywhere in Hong Kong. Their omnipresence is evident in Liu Yichang’s classic The Drunkard (1963), which opens with a writer and alcoholic frequenting a nightclub for drinks and chatting up the promiscuous female servers. Evoking the scene, Liu writes, ‘Not all those on the prowl are brave souls; especially in the neon-lit thickets, the innocents on the swing set are few and far between.’ The intoxicating neon drips from the tip of Liu’s pen.

Cinematic World, Aesthetics of the Mise-en-Scène

In cinema, one can imagine how the neon sign, as a prominent fixture of the Hong Kong streetscape, can be found in just about any film shot here. Most film critics would readily cite the works of Wong Kar-wai (As Tears Go By, 1988; Chungking Express, 1994; andFallen Angels, 1995) as examples of the aesthetic adaptation of the neon-lit urban backdrop. But for me, the most outstanding example — both in terms of artistic intention and visual execution — is Clifton Ko’s Devoted to You (1986). Two secondary school classmates, rich girl May Lo and poor girl Rachel Lee, start dating vacationing Canadian university student Jacky Cheung and biker-gangster Michael Wong, respectively. In a passionate kissing scene, Lee and Wong, set against a gigantic bright-red ‘TDK’ neon signboard, cuddle in a dimly lit corner on a rooftop, surrounded by fishbone TV antennas. Lasting just over two minutes, and ending with the neon signboard going black, the scene stands in contrast to the rendezvous scene between Lo and Cheung, which is set under the mellow lighting of the Charter Garden fountain. In film, neon lighting, especially in red, effectively sets the mood for blazing desires.

… neon lighting, especially in red, effectively sets the mood for blazing desires.

Legends of the Fallen City, Urban Nocturnes

As for Cantopop, ‘neon’ frequently appears in the lyrics of popular songs, such as Jacky Cheung’s ‘Loving Each Other’: ‘Each and every light | Slowly fades away. | The city’s hustle and bustle | Finally quiets down. | Neon lights glow in the dusk every day, | Resting on a hard day’s night.’ The song’s popularity owes much to it being Jacky Cheung’s romantic hit and less to the mention of neon lights. The neon light, at best, shows up in cameo, such as in the 1980s oldies ‘Streaks of Rain’ by Hacken Lee and ‘Shadow Dance’ by Alex To, as well as in recent hits such as ‘One Night City’ (2011) by Ken Hung. But I will always remember Mavis Hee’s ‘The Fallen City’ as one that truly and tightly ties the neon light to the imagery of the city: ‘Legend has it that a city will fall at the tears of infatuation. | The world turns forlorn as the neon lights go off; | Fireworks are spent and music stops. | The finale seems ever more touching.’ On the surface, the song may seem to be just another love ballad, but lyricist Wyman Wong references the neon light throughout, rendering it ‘the backdrop of the vanity fair that has run its course’. Even the most magnificent neon sign will eventually burn out and the most touching tune will end. Given this conclusion, it is difficult to tell whether the song is about the fate of a romance or of the city.

Another memorable title that I grew up listening to was Tat Ming Pair’s ‘It’s a Starry Night’, which begins with a neon reference: ‘Neon lights shine through the night, | Upon the whole city. | Lingering on the road, | All I look for this midnight | Is a new direction.’ Various types of lights (traffic lights as well as lights on lampposts, waterfront promenades and in parks, etc.) flash past as one drives down the streets. Yet, these incandescent glitters cannot mask the feeling of chilly bleakness. And a child in despair longs for the darkness of midnight more than ever. The last few lines of the song capture the metropolis in a snapshot: ‘Please take a last glance at this glamorous city, | Then march forth. | With doubts deep down, | I fear this glittering city | Has seen its last hurrah.’ These lyrics by Keith Chan sound alarmingly like a final judgement on Hong Kong during its pre-handover transition, amid all the questions and uncertainties. The song’s MTV, released in 1987, is also memorable for featuring the lead singers, in all black clothing complete with shades, weaving in and out of traffic through neon-lit streetscapes, including that of Nathan Road.

The neon light, at best, shows up in cameo…

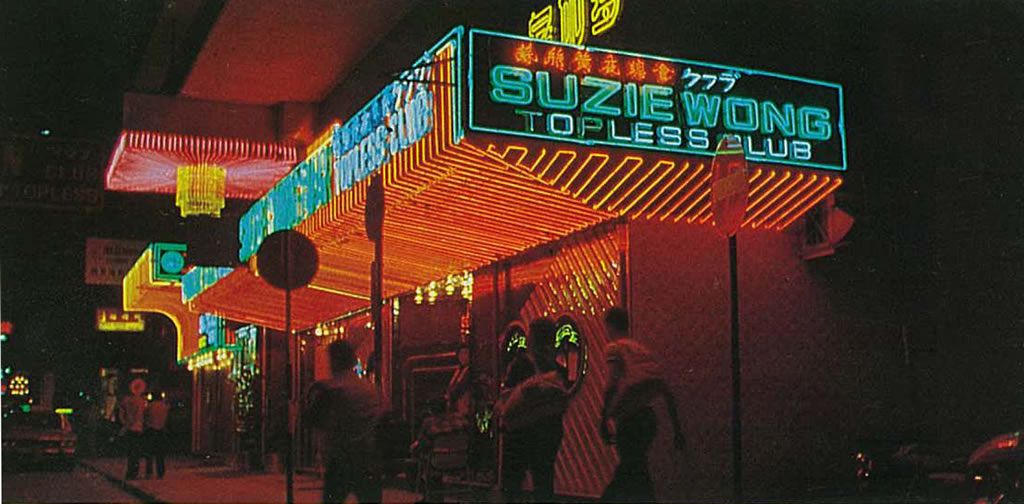

Soft Disappearance, Gradual Transition

Every golden age is bound to meet its decline, much like Walter Benjamin sees ghostly ruins lurking at the zenith of capitalism. Any trendy product of the city will inevitably show its age as the decades pass, much as dust has gathered on the neon signs above retailers selling bird’s nests, herbal tea and long johns, as well as pawn shops, mahjong parlours, old-style steakhouses and nightclubs. The titillating neon signs on Wanchai’s Lockhart Road remind us of the world of Suzie Wong, when US Navy crews spent offshore leave there. Like a woman whose prime has passed, the neon signs there have largely retained their charm, though slack maintenance results in missing strokes or whole radicals, radiating an unexpected sense of humour and decay in the city’s forest of lights and shadows. To be sure, some have already served out their useful lives, such as the iconic ‘Yue Hwa Chinese Products Emporium’ sign, which is long gone. Some shops, though, sport both neon and LED signs, illustrating generational succession in the same space. Others, such as McDonald’s, clearly mark the new and the old: the old signs have red and yellow neon lighting, whereas the new signage is fitted with standard-issue yellow and white spotlights. Having existed for generations, through prosperity and radiance, decay and desolation, and serving to stoke and create desire, the neon sign has slipped into disappearance, unexpectedly forming an imagery of nostalgia and melancholy. Yet, it is too soon to say Hong Kong’s neon lights have lost their lustre, as signs still beam in abundance on the streets. Disappearance is a gradual kind of transition, and fading can take ages. When the neon sign has finally completed its historical mission, its demise will surely not happen overnight.

Liu Yichang’s novel The Drunkard opens the story with a term ‘neon jungle’, symbolising the red light district.

Liu Yichang’s novel The Drunkard opens the story with a term ‘neon jungle’, symbolising the red light district. Directed by Wong Kar-wai, the film Fallen Angels use neon signs in Wan Chai as an urban backdrop; Courtesy: Block 2 Pictures Inc. All rights reserved.

Directed by Wong Kar-wai, the film Fallen Angels use neon signs in Wan Chai as an urban backdrop; Courtesy: Block 2 Pictures Inc. All rights reserved. Richard Quine’s movie The World of Suzie Wong popularises Wan Chai as Hong Kong’s red light district. Later, in the 1970s, a nightclub in the area borrows its name from the film and becomes a local landmark; Courtesy: Frank Costantini and Kirk Kirkpatrick

Richard Quine’s movie The World of Suzie Wong popularises Wan Chai as Hong Kong’s red light district. Later, in the 1970s, a nightclub in the area borrows its name from the film and becomes a local landmark; Courtesy: Frank Costantini and Kirk Kirkpatrick