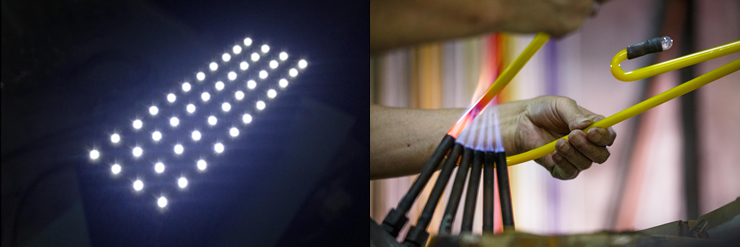

Since the 1990s, the production of neon signs in Hong Kong has undergone a rapid decline. While they still help to animate the city’s brightly lit streets, neon signs have lost their once favoured status, giving way to other outdoor lighting technologies such as fluorescent lightboxes and, especially, LEDs. Indeed, the latter has transformed the urban nightscape with its pixel-like collages of tiny white and coloured bulbs—evidencing a range of economic, regulatory, social and technological shifts that have muted neon’s once-brilliant glow.

The Emergence of LEDs

On the one hand, neon signs have fallen victim to one of history’s greatest culprits: obsolescence brought about by newer, more efficient technologies. In the previous century, soon after World War II, neon signs began to be replaced by backlit, fluorescent lightboxes that, among other things, offered greater graphic possibilities at a larger scale conducive to the age of the automobile and its need for readability at faster speeds and from greater distances. More recently, however, another technology has come to the fore: LEDs (Light Emitting Diodes). While they first made their appearance in 1962—though they were largely limited for use as indicator lights on consumer electronics due to their low light levels—LEDs had over time become affordable and brighter alternatives to neon tubes. Consisting of single-point semi-conductor light sources, usually arranged in a dot-matrix-like grid, LEDs offer more flexible opportunities for display, at sometimes high resolutions, as compared to the limitations of bent neon tubes. At the same time, LEDs provide a potentially limitless palette of colours, whereas the range for neon tubes, restricted to the noble gases that fill them, is much narrower.

Moreover, while the production costs for LED signs are comparable to those for neon signs, LEDs’ greater energy efficiency makes them less expensive to run in the long term. Maintenance costs are also lower as compared to neon signs, which require regular upkeep and, occasionally, replacement of their neon tubes. 1 Finally, LEDs burn up to five times brighter than neon signs, making them more desirable for businesses seeking to grab the attention of customers and passersby. Altogether, these factors have given LEDs a sizable technical and economic advantage over neon.

Regulatory and Legal Issues

Since the early 20th century, neon signs have been an indelible part of the modern city—in both reality and the imagination—and have even been promoted by tourism boards as local attractions. Nevertheless, governmental and regulatory frameworks have not always been receptive to neon signs. While not referencing neon signs in particular, as early as 1912, the Hong Kong colonial government enacted the Advertisement Regulation Ordinance to regulate the use of advertisements ‘which affect injuriously the amenities of any public place or disfigure the natural beauty of a landscape or of the waters of Hong Kong or of the clouds or sky’ 2. Anyone who failed to comply, or breached any regulation made under this ordinance, was liable to a fine; an order for the removal of the offending sign; and potentially even imprisonment for up to three months. Though the enforcement and consequences of violating the ordinance were not severe enough to impede the speedy erection of unauthorised signs, the Advertisement Regulation Ordinance nevertheless reflected the government’s intention to regulate on an aesthetic level.

“… governmental and regulatory frameworks have not always been receptive to neon signs.”

In 1920, eight years after the Advertisement Regulation Ordinance, the colonial government also introduced Advertising By-laws that provided clear definitions for ‘neon signs’ in Hong Kong as well as guidelines for their installation. Those who wanted to affix or exhibit any neon sign had to apply for a license from the Urban Council, with approval documents from the Commissioner of Police, the Chief Officer of the Fire Brigade and authorised architects. This unclear division of work between the government departments complicated the license application process and hindered the effectiveness in regulating the unauthorised signs. It also further obstructed the introduction of a neon tax proposed by the Urban Council in 1949: a fee of $100 per annum for the first 20 square feet of the sign, plus an additional $100 for every 10 square feet thereafter, as part of a revenue-generating initiative by the government. However, due to technical difficulties in implementation and resistance from the neon sign industry, the proposal was dropped in 1950.

The goals of the government in regulating signs have therefore changed through the years, from aesthetic outcomes to economic ones. But more recently, the regulatory challenges to neon signs have been rooted in concerns for public safety. Laws and guidelines such as the “Guide on Erection & Maintenance of Advertising Signs,” introduced in 2003; “Guidelines on Industry Best Practices for External Lighting Installations,” in 2012; and “Validation Scheme for Unauthorised Signboards,” launched in 2013, all reflect a governmental emphasis on public safety by calling for the dismantling of signs that exceed specified dimensions and implementing safety checks every 5 years. One of the effects has been an acceleration in the rate of sign removal, at approximately 3,000 unauthorised signboards per year since 2006.

“The goals of the government in regulating signs have therefore changed through the years, from aesthetic outcomes to economic ones. But more recently, the regulatory challenges to neon signs have been rooted in concerns for public safety.”

Positive Impressions

Cultural shifts are also a factor in neon’s decline. When they first appeared in European and American cities at the beginning of the 20th century, soon to be followed by urban centres in Asia, neon signs were associated with prosperity and modernity. While this began to change earlier in the West, it was still the case in Hong Kong as recently as the 1990s. Nevertheless, neon’s eventual associations with seediness and the risqué have lessened its appeal among businesses that wish to project a more wholesome and trustworthy image.

Moreover, other societal trends have perhaps played a role as well. For one, the function and perception of signages in general have undergone a significant evolution. In the past, people relied on signs to find their way, or to affirm that they were in the most exciting destination in town. Today, people rely on their smartphones, with applications such as Google Maps, Foursquare and OpenRice acting as their guides. Finding one’s way has become less a matter of looking up than of looking down on a four-inch screen. At the same time, the faster rate of turnover among businesses has lessened shop owners’ willingness to invest in elaborate signages.

Cities have always been both engines and mirrors of technological, social and political transformations. To the extent that neon signs have long been inextricable from the city, it is perhaps ironic that one of the city’s greatest attributes—change—is now leading to the decline of neon signs themselves. However, the disappearance of neon signs does not necessarily portend the extinction of their craftsmanship. Perhaps the influence of neon signs is simply being exerted in other realms, where they will continue to brighten our visual culture.

“Cities have always been both engines and mirrors of technological, social and political transformations. To the extent that neon signs have long been inextricable from the city, it is perhaps ironic that one of the city’s greatest attributes—change—is now leading to the decline of neon signs themselves.”